When Kate Horsfield, B. Ruby Rich and I set Lesbian Home Movie Project in motion, we didn’t expect to find a whole lot of amateur lesbian moving images. We just really loved what serendipity had sent our way — our 16mm Ruth Storm Collection* and Caren McCourtney’s Super 8 — and we thought finding whatever else might be out there well worth the trouble of looking for it. Be a small project, we thought. Easy. Fill a gap. Perfect for a cadre of three. Fun!

For a while it went as expected. A few reels here, a few reels there. Ahem. There was a surprise in the wings.

As videotape technology had advanced and videocameras gotten cheaper, more and more lesbians had acquired them, often second-hand. That changed everything.

Film had been expensive and film reels for amateur use were very short. But the killer, from lesbians’ perspective, was reels had to be sent to labs for developing. Human eyes were involved in that: not just lab techs’ eyes, bad enough, but, everyone feared, police and the FBI. The few lesbians who chanced that shot very carefully. Caren McCourtney did film a kiss, and maybe more (maybe a threesome?) The room was very dark. Hard to tell for sure. But she was near singularly bad ass.

Videotape removed the necessity of risking sending media to a lab but early videotape cameras weren’t perfect for general use. They were unwieldy and so was the tape itself, which also cast an image it appears only cognoscenti could love. The images it captured didn’t improve with time. Neither did the medium itself, which stretched and gathered mold spores, glued itself together, and generally misbehaved.

When video cassettes came along, they offered major advantages to lesbian eyes.

Being self-contained meant no more having to guide delicate film & tape through spindles or wind and rewind. No sticky fingers on the medium. Just insert a cassette and press record or play. Yes, after many plays, tape might break. Definitely it would stretch. A major problem, yes. That’s why we digitize before we play tape now, but it didn’t constitute anything near as huge a problem as having to splice breaks. The new technology also made it easy to record sound and lesbians of the lesbian feminist period had a lot to say. Readings, performances, speakouts, and demos with podiums abounded. (True, the sound wasn’t great but at least it was there.)

As videocassettes shrank and recorders grew lighter and lighter, related systems also became simpler to operate. Light was more of an issue than many newbie, amateur videographers apparently understood but even when a reel was too dark, at least at least it captured a suggestion of what had occurred, a great thing in itself.

Another big advantage: videocassettes could record & play for a really long time. Standard play was two hours, long play up to four hours, and the now dreaded extended play. . . six hours. (Why dreaded? Length affected quality: the more the compressed onto a tape, the less good it looked later. Also the more likely to break.) But a videographer could just put a camera down on a stool and leave it. Pick it up 5 hours later. (LHMP’s collections include one tape of almost nothing but midriffs. Got to love it. Well, I do.)

By far the biggest draw for lesbians behind and in front of cameras was that video recordings could be replayed as soon as the tape reached its end. Just rewind. One or two could put their heads together & watch a cassette play on the camera screen itself. For a group viewing, a cassette had to be inserted into a player of some kind and projected. Happily, for the most part, players weren’t pricy. Soon almost everyone had one, and neither form of playback required the intervention of a laboratory. So there, spying eyes!

All in all, videocassettes were an ideal medium for the convivial yet sequestered circumstances of developing lesbian communities: dykes who hiked together, camped together, chorused & put on plays, bought tracts of undeveloped or unappreciated land, built home sweet homes, and held festivals, concerts, and parties, so many parties!

A few videographers learned to edit their footage and assembled composite videos to show at celebratory events — birthdays! weddings! cronings! LHMP’s board member Shirley Lasseter’s collection includes many savvy, entertaining composites, even videos capturing old friends enjoying watching their past selves. But most videographers found editing challenging even after LHMP sent digital copies to work with and iMovie made it fairly easy. Maybe most didn’t want to cut. Not one moment, not one face, not one alligator, not one potluck casserole nor kiss.

Gradually video players wore out, technology moved forward again, and lesbian videographers found themselves increasingly unable to watch their own pieces. Enter LHMP’s offer to preserve, digitize, and document lesbian footage for no charge other than allowing us to preserve and document the originals. Right offer, right timing. Our collections ballooned. Today they’re larger than we had ever imagined possible.

By the time pandemic rolled in a decade later, arguably LHMP held the largest collection of lesbian-related home movies and amateur films in the world. We’d never have been able to reach that point without the help of the great Northeast Historic Film’s lab, vaults, and kind, wizardly moving-image-loving staff. It had become apparent, however, that the collection needed a well-funded long-term institutional home in a location scholars & interested lesbians of all ages could access easily so the films and videos collected wouldn’t get lost in the massive shuffle of history, herstory, and their story.

We founders didn’t always agree about everything but there was no disagreement about this. We needed to ensure the footage would survive and be tagged “lesbian.” When Harvard Film Archive agreed to become that home and work with the Schlesinger Library and Radcliffe on our extensive documentation, we said yes without hesitation: Best choice? No. DREAM choice. Phenomenal serendipity.

Once that was agreed, Ruby & Kate retired from the executive board and LHMP moving image makers Janet Prolman — and Shirley Lasseter, lesbian home movie editor supreme, joined. (We also began to assemble an Advisory Board. More on that soon. But they helped too.) Of course, there’s a considerable distance between something that looks good, even almost perfect, and something that floats.

Two brilliant salt-of-the-earth advisors helped a ton: C.K. Ming, who has a wealth of experience with MOMA, South Side Home Movie Project, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), and Center for Home Movies

C.K. Ming

and photographer Angela Brinskele who (with Ann Giagni) shepherded The June L Mazer Lesbian Archives arrangement with UCLA.

At Harvard’s end, Collections Archivist Amy Sloper brought patience, understanding, and more brilliance to the process.

On December 1, 2023, the last person who had to sign the final agreement did. A lot of work ahead to prep our collections and documentation for Harvard’s but it’s all systems go.

It’s not the end of LHMP itself by a long shot. Harvard Film Archive has taken responsibility for preserving all original media as well as maintaining and when necessary updating a full set of digital copies. It will also catalogue and archive our documents and research. For the present, original films and tapes will remain in the wonderful climate controlled vault at Northeast Historic Film, Bucksport, ME, and LHMP is maintaining our Orland, ME, address and will continue to hold a full set of digital copies here at our archive in Blue Hill, Maine. We also continue to collect, license, document, and hold copyright on all our collections (the latter in conjunction with living moving image donors). In other words, yes, we’re still hunting for film & video tape that fits our mission.

In November, I flew to Temple, AZ to share LHMP footage and look for more at Old Lesbians Organizing for Change 2023 Gathering. (Some’s been promised. Fingers crossed!) More research & presentation trips are in the works for 2024. If there’s somewhere you think we should go or you have some footage that’s on point or know where some is, speak up!

* For an account of filmmaker Sheila McLaughlin’s donation of the Ruth Storm Collection which started it all, see https://www.lesbianhomemovieproject.org/about/ as well as the collection itself.

LHMP had planned to go on the road in 2021, screening private treasures we couldn’t stream, seeking more film & tape collections, and expanding our advisory board as the project gathered more friends. The pandemic put a stop to that plan but we’ve been so busy that it’s hard to imagine how we would have pulled the jaunts off in any case. (Gainesville, we’ll get there one day!)

LHMP had planned to go on the road in 2021, screening private treasures we couldn’t stream, seeking more film & tape collections, and expanding our advisory board as the project gathered more friends. The pandemic put a stop to that plan but we’ve been so busy that it’s hard to imagine how we would have pulled the jaunts off in any case. (Gainesville, we’ll get there one day!)

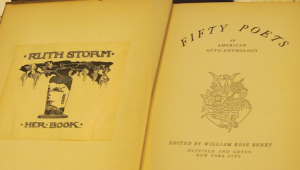

It bounces a little in a breeze. Hard to date and place but we’re still hoping. We even have a clue: a poetry book Ruth inscribed to a lover, now in the possession of that lover’s daughter. Could it possibly include this line from William Cullen Bryant: “the shad-bush, white with flowers, brightened the glen”?

It bounces a little in a breeze. Hard to date and place but we’re still hoping. We even have a clue: a poetry book Ruth inscribed to a lover, now in the possession of that lover’s daughter. Could it possibly include this line from William Cullen Bryant: “the shad-bush, white with flowers, brightened the glen”?